In line with the recent article “Are viruses alive?” I would like to further explore the general nature of viruses. One question that I was recently asked was “does a virus move?” Being that viruses are not technically alive in the sense that we know it they also cannot move in a self-directed manner. This is in stark comparison to some other microbes such as Schistosoma cercariae, a parasitic worm, which is capable of burrowing through intact human skin and gaining access to the vascular system within 5 minutes (1). Thankfully viruses cannot do this, much to our benefit. Because of their very nature viruses cannot mechanically move in a self-directed manner and are subject to movement solely based upon environmental interactions. Essentially, they are not only hijackers who take over cellular processes for their own good, but environmental hitchhikers as well.

One prime example of “hitchhiking” is used by the influenza virus, the causative agent of the common flu that we all know so well. This virus infects the upper airway and lungs and must come into intimate contact with these surfaces to initiate an infection. Since it cannot get directly from one host to another it hitchhikes in the tiny particles of saliva and mucous produced when you sneeze or cough. If you inhale another infected person’s particles it allows the influenza virus direct access to your lung tissue. It can also spread by contacting contaminated surfaces (fomites) and then touching your face, effectively inoculating yourself with the virus. A second example of this is the transmission of poliovirus. This virus infects the intestinal tract and is shed in very large amounts in feces. If a person comes into contact with even trace amounts of these contaminated feces and ingests them a new productive infection begins.

This characteristic of viruses is highly advantageous for researchers as it facilitated the use of the viral plaque assay; one of the standard workhorses of the microbiological laboratory. Since a virus cannot move it only infects cells directly adjacent to those it has already infected. When a virus is diluted down to a very low concentration and added to a single layer of cells you will see first a single cell get infected, begin to produce virus, and die, then the cells around it in an outward fashion forming a circular focus of dead cells known as a plaque. By counting the number of these plaques formed on a layer of cells and accounting for the dilution it is possible to determine the amount of virus in a sample with a good degree of precision. This method is commonly used to determine the titer (infectious particles/volume) of a sample for use in further experiments. While viruses cannot move through the environment on their own, a fact exploited by researchers in the laboratory, they have developed strategies that are intimately tied to their life-cycles in order to get from one host to the next.

1. McKerrow, J. & Salter, J. Invasion of skin by Schistosoma cercariae. Trends in Parasitology 18, 193-195 (2002).

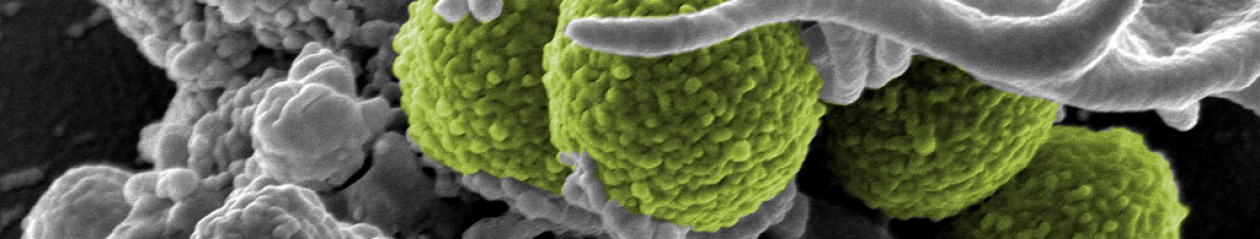

[Featured image from Wikimedia Commons used under Creative Commons License.]

how do they move

so… if they are immobile… and they are not ‘alive’… why do they say a virus can ‘live’ (remain active) for X number of days/hours/minutes on surfaces? What ‘kills’ (renders them harmless) then? Are they physically damaged? Do they become bound to gasses in the environment? Are they damaged by ozone/ions/surface charges??

and how does UV light affect them?

so…. if they are immobile… and they are not ‘alive’… why do they say a virus can ‘live’ (remain active) for X number of days/hours/minutes on surfaces? What ‘kills’ (renders them harmless) then? Are they physically damaged? Do they become bound to gasses in the environment? Are they damaged by ozone/ions/surface charges??

…

and how does UV light affect them? .

Ah, great question! When they say a virus can “live” what they are really saying is that it is still viable in that it is still infectious. They can be rendered harmless/non-infectious in a couple ways. Detergents will disrupt any outer membranes that a virus has, which will render it inactive since it can no longer bind to cells and cause infection. UV light is effective because it causes DNA or RNA damage by way of mutations. Too much UV leads to so many mutations that the viral genetic material is essentially junk and no longer functions.

Viruses are very simple chemically. Think of them as a bunch of macromolecules put together into one structure. Just as any molecule can break down in a certain number of days, so does a virus. This is what people refer to when they say a virus can “live”. “Live” in this case means the “number of days before the virus expires or is cannot operate”.